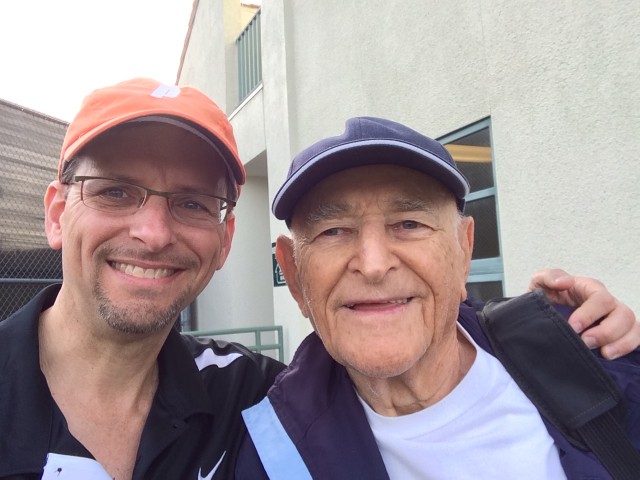

This is my tennis pal, Andy Roth.

I’ve known Andy for nearly twenty years and play tennis with him and a regular group several times a week. He has a wicked forehand, runs down every ball, and never misses a chance to humiliate me with a passing shot, after which he howls with glee.

Here’s how he usually responds when I ask how he’s doing: “It’s a great day, yeah? I woke up above the grass.” Then he chuckles.

This is Andy’s laugh. It’s one of the better sounds in the world.

Andy is 86. But on Friday he celebrated his 69th birthday.

April 11 is what Andy calls his “second birthday”: the anniversary of his liberation from Buchenwald.

Number A8520

Photo: Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-1983-0825-303 / CC-BY-SA

Born in a small town in Hungary, Andy was swept up in the Holocaust at age 15, when the Nazis invaded the country and deported the Jews to concentration camps. He landed first in Birkenau, a subcamp of Auschwitz, where he got his prisoner tattoo and became Number A8520.

It’s hard to see now, but there’s a story behind that: Andy’s cousin fainted when they gave him his prison tattoo. Andy saw what he thought was a barrel of water and plunged his hand in to splash his cousin’s face. But the barrel was full of mustard, which stained Andy’s fresh tattoo yellow.[/column]

Over time, Andy “enjoyed” the Grand Tour of concentration camps: from Birkenau to Auschwitz, then to Buna (another sub-camp), and then by six-day train trip…in an open boxcar…in the middle of winter…to Buchenwald.

More than 8000 prisoners got on that train with Andy; fewer than 500 made it to the end alive.

Buchenwald’s main gate, with the slogan Jedem das Seine (“To Each His Own,” but figuratively “Everyone Gets What He Deserves”).Photo: Wiki-Commons.

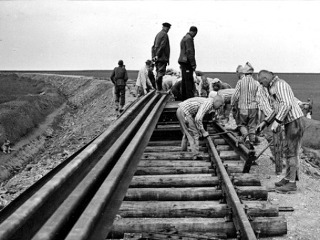

Inmates laying track on the Weimar – Buchenwald line in spring 1943. Photo: Central Construction Management of the Armed SS; Thüringisches Hauptstaatsarchiv Weimar

Buchenwald

The horrors of the concentration camps have been well documented elsewhere. Suffice it to say that Andy endured hardship and brutality that most of us can not even imagine.

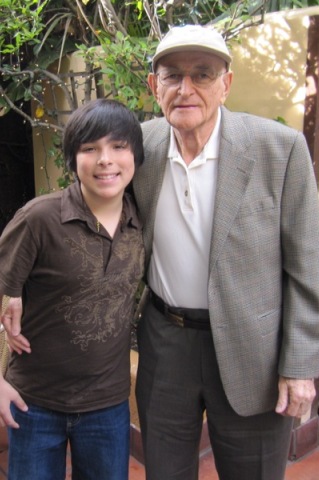

My nephew, Matthew Rogers, interviewed Andy last year by Skype for his school newspaper.

Matthew (12 in this photo but 15 at the time of the interview—the same age as Andy when imprisoned) asked Andy if the movie Schindler’s List had given a realistic depiction of life in the camps.

Andy said it was a good movie about a worthy man, but it couldn’t even begin to approach reality: “If life had been anything similar to what was depicted in Schindler’s List, I would have re-enlisted.”[/column]

He survived through grit, determination, youth, desperation (he once stood up to a machine-gun wielding SS guard and said, “Shoot, or food”; the guard let him have a bit of his soup), kindness (the elders in camp protected the boys when they could), and sheer luck.

Matthew, Andy, tennis buddy Kevin Cronin, me, my brother Steve Rogers (not Capt. America)

Freedom

Liberation came on April 11, 1945.

Here’s Andy’s description of Liberation Day, from Matthew’s interview. (When Andy talks about the prisoners being marched out of camp, what he forgot to say was that they were being marched out to their deaths.)

After the war, Andy spent time in an orphanage in France, learning to live in society again; he and his fellow young survivors, including Nobel Prize-winning author Elie Wiesel, were the subject of the 2002 documentary film, The Boys of Buchenwald. He found work, came to New York, had back surgery to repair broken vertebrae from the camps, and ultimately moved to Los Angeles, where he put down new roots and started a successful carpet business. (One of his first clients was Art Carney from The Honeymooners.)

All along, he perfected his English by solving crossword puzzles and doing the daily Jumble, a practice he continues to this day. He still likes to try to flummox me with stumpers. (“MUTANU” was his latest Jumble challenge.)

I thought a lot about Andy and his remarkable story while I was writing Eleven.

People respond to adversity in as many different ways as there are people. Andy could have let his anger and sadness consume him. But he probably wouldn’t have met his beautiful wife, Ann; had two loving kids, Jeffrey and Lisa; or known his adorable twin granddaughters, Ruby and Olivia.

He would never have known the joy of hitting forehands past me at net.

He would have let three years of misery deny him sixty-nine years of happiness:

.

Zingers

In my book, the old man named Mac quotes something his wife once said: “Better to light a candle than curse the darkness.” I’ve never heard Andy use those exact words, but I know he understands them better than most.

I know it by the way he gets a twinkle in his eye when he’s about to fire out a zinger.

A number of years ago, Andy went back to Buchenwald to visit. Before the trip, he told Ann, “The last time I came to Buchenwald, I had no reservations, and we had to sleep outdoors. This time, we’re staying at the Hilton!”

Happy 69th, Andy.

********************

If you’re interested, here are a few more snippets from Matthew’s interview with Andy.

What today’s young people need to understand:

On immigrating to the United States:

For students who might just be learning about the Holocaust, here are places to go for additional information:

On the West Coast, visit The Museum of Tolerance

On the East Coast, visit the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

Read The Diary of a Young Girl, by Anne Frank

Read Night, by Andy’s blockmate at Buchenwald, Elie Wiesel